We used computers when I was in college… for word processing. Drafting was done on vellum, renderings on Canson paper, and getting to buy some new pens at the art store was the height of excitement.

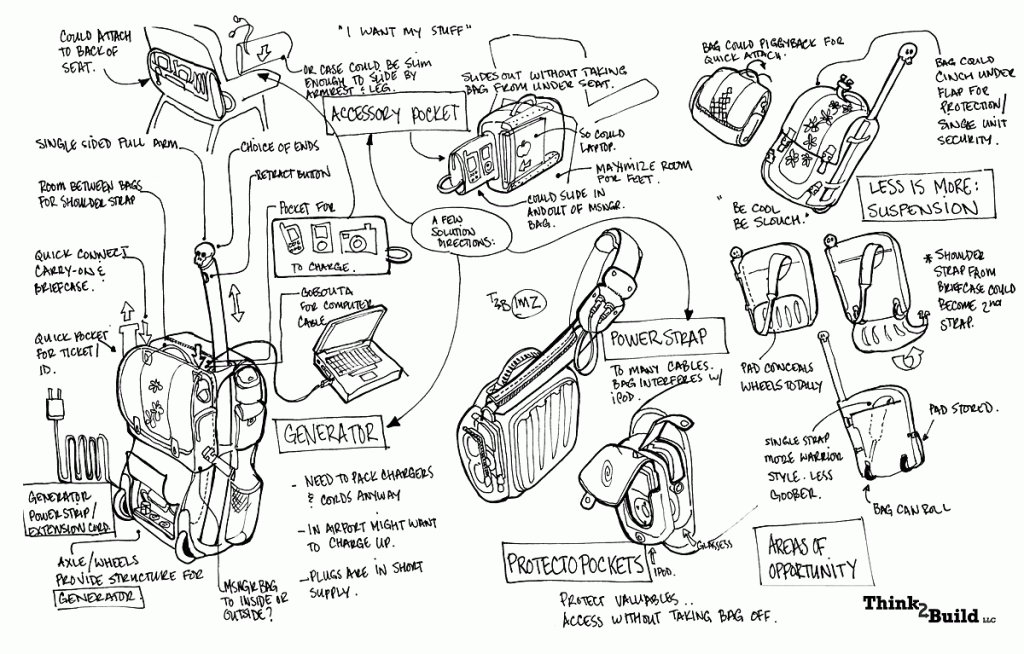

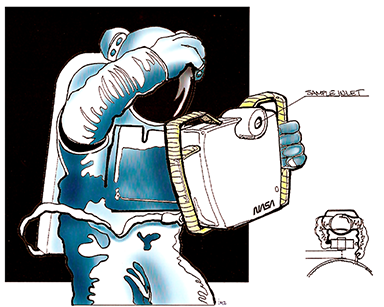

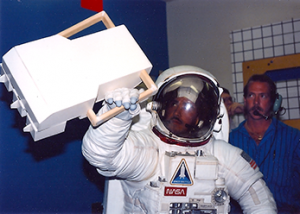

After graduation, my first job was with a technology consulting firm. Just about everyone I worked with was an engineer, many with 20 or 30 years of experience, and everyone was expected to bring something special to the table. Things were old-school by today’s standards; drawing packages were done by hand, checked, and “rapid-prototyping” meant you might only wait a month to get your parts back. In that environment, one of my first vectors of success was in helping people “see” the implications of the decisions they were making. Someone would ask me to draw their idea, and I would give them extra; their idea, and a couple more of my own. Pretty soon people were inviting me to their brainstorms and asking for my ideas up front; There was such a long lag and large investment to produce products that it was critical to aim before the trigger was pulled. That role of “seer” still exists today- the clock just ticks faster…

As the tools of our profession make it easier and faster to create “finished” looking parts and renderings, a lot of engineers and designers skip the sketch/ ideation phase & jump straight to CAD; shortchanging both themselves and their clients on the up-front work which goes into developing well a conceived product. Being able to communicate visually was my first professional opportunity to be heard; working to build your fluency will benefit you every day you practice. A product designer who can’t draw risks being relegated to executing someone else’s vision or becoming entirely irrelevant until all the decisions have been made.

Drawing is a visual expression of your thought process. Efficient, articulate sketching is a great technique to not only generate, but organize, refine, and share ideas quickly, and to explore many directions before investing heavily in detailing a single solution.

In days of yore, industrial designers were the de facto gatekeepers of ideas as we were the ones who could articulate them fastest- to some extent, we had everyone else over a barrel. What I see these days is it’s computer tools which have many designers over a barrel. As tools have lowered the barrier to express ideas, designers need to take a little more responsibility. Today designers need to advocate more, not just present images, but organize and make sense of the idea space for the team- tougher, but a much more valuable skill set in my opinion. What’s interesting is that in either scenario drawing is still fundamental to how others will perceive your grasp of the situation.

In days of yore, industrial designers were the de facto gatekeepers of ideas as we were the ones who could articulate them fastest- to some extent, we had everyone else over a barrel. What I see these days is it’s computer tools which have many designers over a barrel. As tools have lowered the barrier to express ideas, designers need to take a little more responsibility. Today designers need to advocate more, not just present images, but organize and make sense of the idea space for the team- tougher, but a much more valuable skill set in my opinion. What’s interesting is that in either scenario drawing is still fundamental to how others will perceive your grasp of the situation.

Strong rapid sketching skills can help your ideas be heard. help to organize your thoughts, allow you to quickly ideate and communicate, and allow you to clearly and efficiently document concepts. When you get good at it, you’ll be able to draw as you think- which allows you to forget about the act of drawing and focus on articulating what it is you want to say. So what would I hope your takeaway be? Drawing is a developed skill- you’ll get better with repetition, and Practice, practice, practice.

Just like a game of Pictionary, the trick to sketching is not to make the most elaborate drawing you possibly can, but to figure out how to communicate your idea as quickly and efficiently as possible. This is particularly crucial when you’re brainstorming, and afterwards when you’re sifting through the ideas generated. While you’re up at the whiteboard, you should be focused on how to cut to the heart of the kernel of your idea. If it takes you five minutes to explain your concept you’ll loose people’s attention, and if you’re sketching in your notepad trying to work through a concept, that means you’re not participating in the discussion at hand.

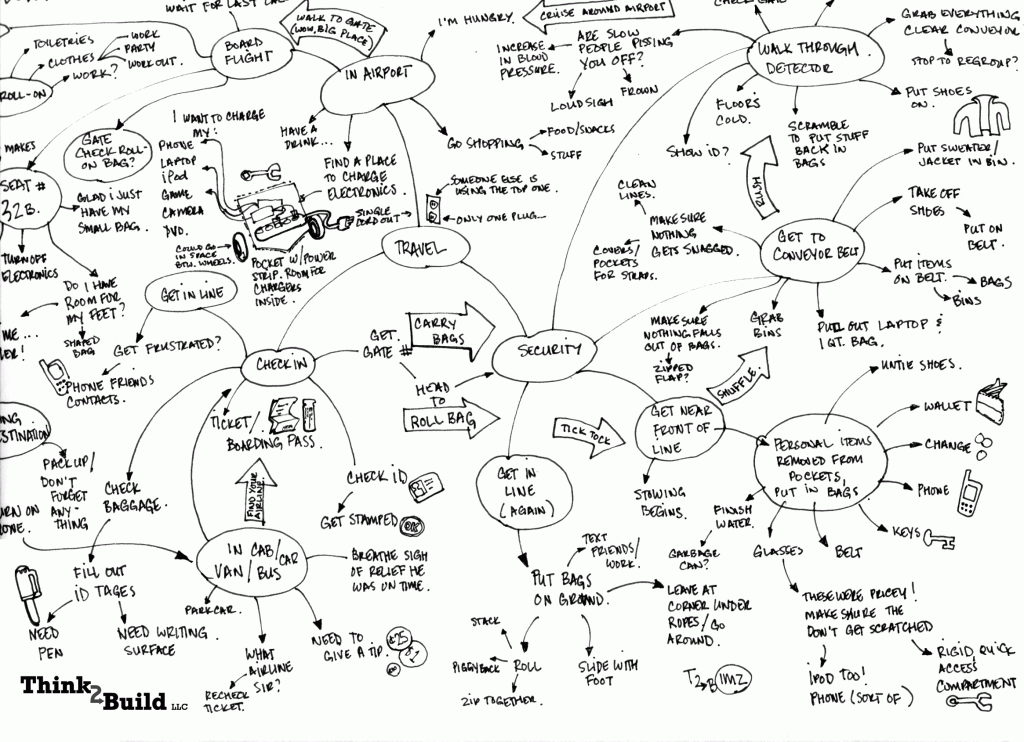

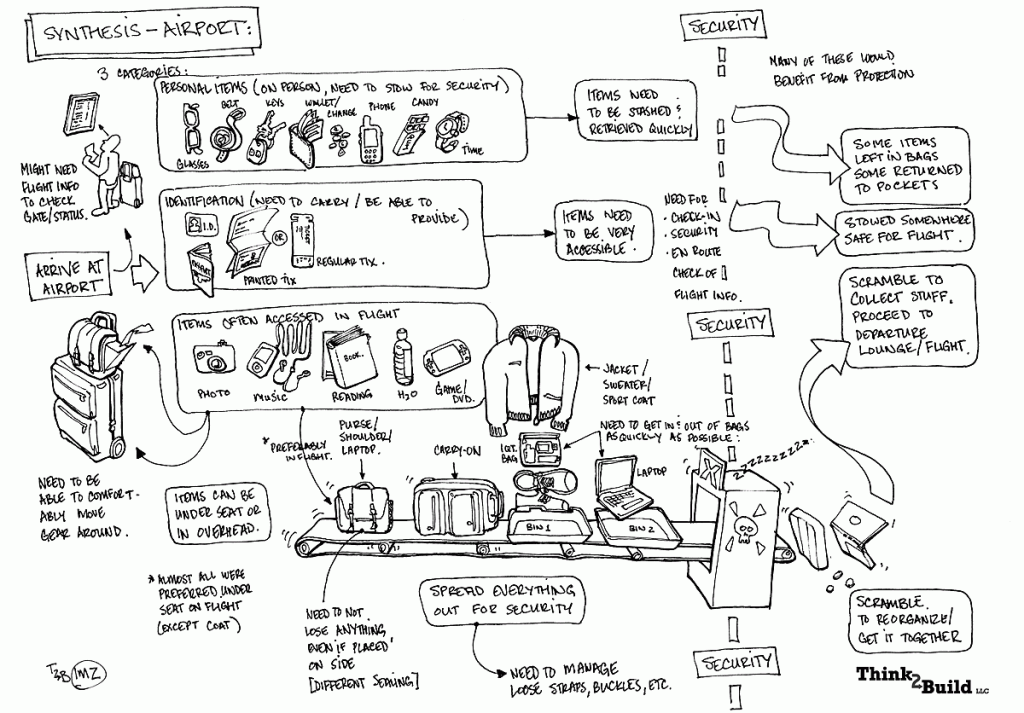

What I like about Mind Mapping is that it’s stream of consciousness- probably the closest I get in my day to the doodling I did on my jeans when I was little (used to drive my mom crazy). In not being precious about a sketch early in the process, we get a little extra freedom to wing it; which can often lead us in interesting directions.

At the start of a project we typically immerse ourselves in the context of our user and sift through the results for patterns in behavior, areas of opportunity to improve a user’s situation, and opportunities to streamline their experience. As we begin to develop our understanding, I find myself continuously sketching- words, scribbles, details, whatever it takes to block out an idea.

Much of this background work doesn’t make it into our outward facing work product, but it forms the foundation for everything we do subsequently; the clearer we are in our own heads, and as a team, the better we’re able to provide value to our clients.